The Atlantic Ocean is getting wider every year, Researchers have finally figured out why

Here is why the Atlantic Ocean is getting wider every year

- Tectonic plates under the Americas, Europe, and Africa are separating as the Atlantic Ocean grows wider.

- A 2021 study suggests atypically hot material, 410 miles underground, is rising and forcing the plates apart.

- “This is what makes this result exciting because it was completely unexpected,” one expert said.

The tectonic plates undergirding the Americas are separating from those beneath Europe and Africa. But precisely how and why that is happening was a mystery to scientists, since the Atlantic doesn’t have the same dense, subducting plates that the Pacific does.

A 2021 study published in the journal Nature suggested the key to the Atlantic’s expansion lies beneath a large underwater mountain range in the middle of the ocean.

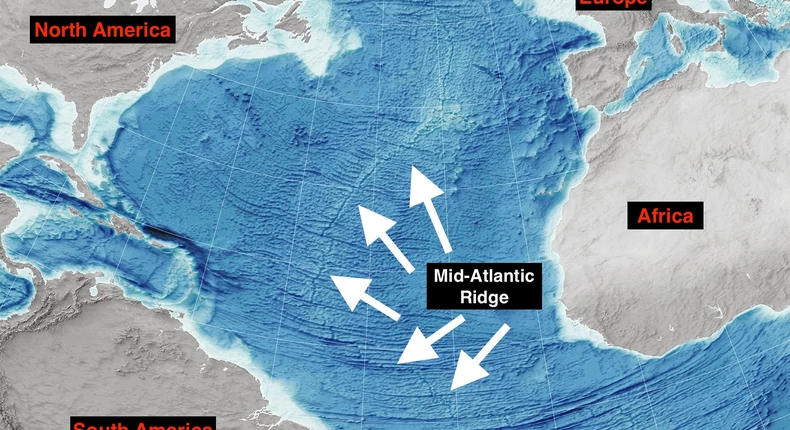

The set of mostly undersea peaks, known as the Mid-Atlantic Ridge (MAR), separates the North American plate from the Eurasian plate, and the South American plate from the African plate.

The researchers behind the study found that material from deep within the Earth is rising to the surface under the MAR, pushing the plates on either side of the divide apart.

The Atlantic seafloor is spreading

The mid-Atlantic ridge, seen in deep orange, on a NASA Earth Observatory bathymetry map.NASA Earth Observatory maps by Joshua Stevens, using data from Sandwell, D. et al. (2014)

A 1,800-mile-thick, mainly solid mantle surrounds the Earth’s core, which is as hot as the surface of the sun.

Fragmented into tectonic plates, the Earth’s crust fits together like a puzzle. These plates interact in various ways, moving together or apart or sliding under one another.

Volcanoes are one way magma can bubble up from inside the Earth. Seafloor spreading, which occurs at divergent tectonic plates that are pulling apart like the MAR, is another. Another way is below the crust where, hot, softened rock rises from the mantle, and convection currents pull it toward the surface.

Generally, any material oozing upward under tectonic boundaries like the Mid-Atlantic Ridge usually starts from the mantle very close to the Earth’s surface, about 3 miles below the crust. Material from the lower mantle, the part closest to the core, isn’t generally found there.

But the 2021 study found that the Mid-Atlantic Ridge is a convection hotspot.

The researchers measured geologic activity across a 621-mile span. They dropped 39 seismometers under the waves in 2016, then left them for a year to collect data from earthquakes around the world.

The part of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge where University of Southampton researchers deployed earthquake-measuring instruments.University of Southampton

Seismic waves reverberating through material in Earth’s core offered scientists a peek into what was happening in the mantle under the Mid-Atlantic Ridge.

The group found that magma and rock from 410 miles under the crust can push their way to the surface there. That upwelling of material is what is spreading the tectonic plates — and the continents on top — apart at a rate of 1.5 inches (4 centimeters) per year.

“Upwelling from the lower to the upper mantle and all the way up to the surface is typically associated with localized places on Earth, such as Iceland, Hawaii, and Yellowstone, and not with mid-ocean ridges,” Matthew Aguis, a seismologist at Roma Tre University and a co-author of the study, told Insider in 2021. “This is what makes this result exciting because it was completely unexpected.”

Often, material trying to make its way from the lower to upper mantle is hindered by a band of dense rock known as the mantle transition zone, between 255 miles and 410 miles under our feet.

But Agius and his colleagues estimated that beneath the MAR, temperatures in the deepest part of that transition zone were higher than expected, making the zone thinner in the area. That’s why material can rise to the ocean floor more easily there than in other parts of the Earth.

Solving a geological mystery

One of the remote seismometers deployed by University of Southampton scientists in the Atlantic Ocean.University of Southampton

The discovery helped solve a long-standing geological puzzle.

Typically, plates move under the force of gravity as it pulls denser parts of plates into the Earth. But the plates that surround the Atlantic Ocean are not as dense, making scientists wonder what’s triggering these plates to move if not gravity.

The research suggests the upwelling of material from deep within the mantle could be the engine of that Atlantic expansion.

Catherine Rychert, a geophysicist from the University of Southampton and a co-author of the study, said this process started 200 million years ago. But someday, the rate of expansion could speed up.

Also Read: Shackleton’s lost ship is FOUND: Endurance is discovered at the bottom of Antarctica’s Weddell Sea, 107 years after it sank – and it’s still in remarkable condition

“Most probably the rate will remain the same during our lifetime. However, it is likely the rate will change over millions of years because it has varied in the past,” Rychert told Insider.

Correction August 22, 2023: An earlier version of this article misstated how subduction zones affect plate tectonics and oceanic expansion. This article was first published in 2021 and has been updated.